I am very excited to be able to welcome musician and mixologist Matthew Guerrieri, a.k.a. Soho the Dog, into the Kitchen. What began with me pestering him for a hot toddy recipe transformed into me pestering him for an entire post, and boy did he deliver. Please enjoy, and big thanks to Matthew–for his wit, his knowledge, and his willingness to handle flaming alcohol in the name of thorough recipe testing.—Molly

In 1805, having become the first professor of chemistry at Yale University, Benjamin Silliman traveled to the British Isles to get up to international speed on the subject he had been hired to teach. Silliman also took the opportunity to observe the social mores of his hosts, duly reporting the habit at the end of dinners (“when they are meant to be hospitable”) of “the drinking of hot toddy.”

A pitcher of hot water is placed upon the table, and each guest is furnished with a large foot-glass holding nearly a pint, in which he mixes his water, spirits and sugar, in such proportions as he pleases; whisky is preferred on these occasions, but that of the highlands, which is the best, is so expensive, in consequence of the excise, that it is not universally used.

Each foot-glass has a small wooden ladle, which is employed to dip the hot toddy out, into wine glasses, from which it is drunk.

Silliman, the founder of the American Journal of Science and the first man to distill petroleum, fairly sized up the hot toddy. “[I]t may well be presumed, that the fumes of such a hot inebriating mixture, must occasionally turn the brains of parties not restrained by considerations of decorum or of religion,” he wrote. “And indeed, among the most sober people, it is easy to perceive some exhilaration produced by the hot toddy, as they sit and sip from hour to hour.”

The hot toddy—alcohol, sugar, hot water, and (sometimes) lemon—is, indeed, conversational fuel, a drink designed to be nursed through an evening’s badinage. It also defies formula, encouraging each drinker to adjust to both their own preference and the needs of the moment. What kind of spirits? How much hot water? (I like a 2-to-1 water-to-alcohol ratio, but that’s just me.) How sweet? (I like a half-teaspoon of sugar per ounce of water, but that’s just me.) Citrus or no citrus? (I like to boil the water with a slice of lemon, but, again, &c., &c. Incidentally, true drinking savants may insist that a toddy with lemon is properly called a skin. If you have constructed your toddy well, such captiousness will not bother you in the least.)

And the hot toddy, in its heady simplicity, is one of the last remaining links to the incunabula of pre-19th-century drinking habits, a cocktail that pre-dates the very term. Start tinkering with hot toddies, and you can start teasing out connections, tracing the crooked path of history.

Follow the path far enough back, and you end up in India. “Toddy” was originally the term for the sap of the Indian coconut tree, left to ferment in the sun. Sir Thomas Herbert, Gentleman of the Bedchamber to King Charles I, described it this way in 1638:

The Toddy Tree is not unlike the Date or Palmeto, the Wine is got by pearcing and putting a Jar or Pitcher under, that the liquor may distill into it…. The Toddy is like Whay in colour, in taste and quality like Rhenish wine, at first draught uncouthly relisht, but every draught tasts better and better, and will easily inebriate; a little makes men merry; too much makes them mad; extreame is mortall: in the morning tis laxative; in the eve costive; at midnight dangerous.

That last assertion was neither license nor euphemism, if one believes John Ovington, who, in his famous account A Voyage to Surratt In the Year 1689, noted the risks of toddy:

Several Europeans pay their Lives for their immoderate Draughts, and too frankly Carousing these chearful Liquors, with which when once they are inflam’d, it renders them so restless and unruly, especially with the additional heat of the Weather, that they fancy no place can prove too cool, and so throw themselves upon the ground, where they sleep all Night in the open Fields, and this commonly produces a Flux, of which a multitude in India die.

An irony, given the hot toddy’s later medicinal reputation. (It should be noted: the appearance of spirits and hot water in an abundance of 19th-century medical journals aside, a hot toddy will not actually cure the common cold, and while it will make the patient feel terrific for a few hours, the chance of feeling worse once the toddy wears off is, alas, all too present, leaving the prospect of a) penitence or b) maintaining a steady dose of hot toddies for the duration of the illness. Given—as I have been led to believe by Dickens and Poe—the comparative damp and filth of the 19th century, one can imagine people drinking hot toddies continuously from cradle to grave. I do not doubt that this happened.)

Toddy, properly distilled into brandy-like form, was called arrack—as was various other distillations from Southeast Asia, of sugarcane, of rice, of fruit. (In some sources, “toddy” becomes a generic term for anything distilled into arrack.) In the 19th century, arrack was a de rigueur ingredient for punch—the possibly spurious etymology of “punch” as deriving from the Hindi panch, or five, is derived from the basic five-ingredient punch recipe: arrack, tea, sugar, water, lemon. I haven’t found any evidence that anybody actually drank arrack by itself in hot-toddy form, but that won’t stop me from trying it.

Now, to the best of my one-day’s worth of Internet-sourced knowledge on the subject, coconut-based arrack is not commercially available in the United States. What is available is Batavia-Arrack, distilled from a sugarcane-rice base. Eh, close enough.

Alternate History Hot Toddy

4 oz. Water

2-4 tsp. Sugar

Slice of lemon

Boil together. Pour over: 2 oz. of Batavia-Arrack

The result: A strong toddy, and one displaying the drink’s tendency to amplify rather than subsume the qualities of its base spirit. Batavia-Arrack is kind of like white rum, but with an oilier feel and a bit of sake-like bread-y sweetness from the rice, both of which boost the richness of this toddy. There’s a lot of burn up front—it was actually turning my tongue numb, almost like a Szechuan peppercorn—but goes down smooth and lastingly warm.

Probably in much the same way that India’s name was applied to the West Indies, the term “toddy” somehow was transferred from its coconut-sap origins to a concoction that also went by the name of “bumbo,” a drink that at least bears a family resemblance to the modern hot toddy. It’s also, perhaps, when the qualifier “hot” became attached. In his 1784 book A Tour of the United States, J. F. D. Smyth relates the typical daily routine of the American “gentleman of fortune” (read: plantation owner) in the South:

[B]etween twelve and one he takes a draught of bombo, or toddy, a liquor composed of water, sugar, rum, and nutmeg, which is made weak, and kept cool

If a toddy was by definition a cool drink, one would, presumably, have to get specific about a hot variant. (Bumbo was, according to common legend, a favorite drink of Caribbean pirates, and certainly seems to have been prevalent there—Tobias Smollett’s picaresque naval satire The Adventures of Roderick Random, published in 1748, gives the recipe. The name, though, might derive a particular kind of drinking cup, made from the shell of a snail: as early as 1612, one can find Angelo Grillo, Italian cleric and poet, friend of the composer Claudio Monteverdi, telling of receiving “a gift, a shell [Cochleam] from the Indian sea, which they call Bumbo,” a cup of “the sort you should have at a banquet.” Which may explain the word’s double-life as a slang term, as explained by Francis Grose in A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785):

BUMBO, brandy, water, and sugar; also the negroe name for the private parts of a woman.

A related usage applied the term to the rear end—a possible genesis of our modern bum.)

The rum toddy reached its apotheosis at the hands of the legendary Charles H. Baker, Jr., playboy and epicure, who included in his collection The Gentleman’s Companion the Baker “Horse Collar,” “ORIGINATED,” Baker wrote in his inimitable way, “by the AUTHOR, A.D. 1935, upon RUNNING into STONINGTON, RHODE ISLAND, ahead of a HOWLING NOR’EASTER when HEADING SOUTH from LAWLEY’S YARD to FLORIDA in MARMION“. (His yacht, naturally.) Baker’s recipe:

The Baker “Horse Collar”

“Tin cups for mariners, silver julep cups for fancies

Carta de Oro Bacardi, Jamaica, Barbados, or Haitian rum, 2 jiggers

Orange peel, 1 to each cup, cut in unbroken spiral

Brown sugar, 1 tsp per cup

Whole cloves, 6; or powdered clove, 1/4 tsp per cup

Boiling water, enough to fill

Butter, 1/2 tsp, optional

Photo by Matthew Guerrieri

Line cups with spirals of orange peel, first dipping them in rum to moisten. Dust sugar on peel, then cloves the same. Put a jigger of rum in each cup, put cups on hot stove, and after a moment set aflame. Let burn until edges of peel start to brown and sugar to caramel. Blow out. Take off stove, add other jigger of rum, fill up with hot water, give a brief stir and serve—either with or without a lump of butter on top the size of a hazelnut.”

(Being neither mariner nor fancy, I made do with a stainless steel cocktail shaker. I did manage to get the peel off the orange in one piece. However, not being keen on the idea of putting flame-hot metal near my mouth, I transferred everything into a mug.)

The result: This is a good one, and not just due to the theatricality of its construction. Baker’s drinks aren’t always the subtlest things, but the Horse Collar is more delicate than it reads, the brown sugar and burnt caramel blending with the vanilla overtones of the rum, the oil from the orange peel lending a faint tropical note, the cloves perking up the aroma. Plus: fire!

One of the more common variants of the hot toddy today uses tea in place of water. I can’t find a specific hot toddy recipe using tea prior to the 1940s or so, but that doesn’t mean the idea isn’t venerable. If you remember the five-ingredient punch prototype, you realize that such toddies are really one-glass-at-a-time versions: punch à la minute. The Hammarubi of cocktail writers, Jerry Thomas, starts his classic 1862 manual How to Mix Drinks, or, The Bon-Vivant’s Companion with a chapter on punches, many of which are mixed by the glass. And the terminology is slippery, for instance: “In making hot toddy, or hot punch,” Thomas writes, “you must put in the spirits before the water: in cold punch, grog, &c., the other way.” (Elsewhere, Thomas reaffirms the notion that punches and toddies and the like are resistant to precise formulae; my favorite is his entry for Scotch Whisky Punch: “As it requires genius to make whiskey punch, it would be impertinent to give proportions.”)

So here’s an improvised one, halfway between a toddy and a punch. (Terminology alert: according to Thomas, the inclusion of nutmeg makes this one technically a sling.)

Hot Bourbon Toddy-Punch-Sling

3 oz. water

1-3 tsp. sugar

Slice of lemon

Boil together. Add to: 2 oz. brewed tea (black or green, your call)

Add: 2 oz. bourbon

Grate over the top: Fresh nutmeg

The result: Substantial and smooth, edging into an almost dessert-wine quality. A lot depends on how strong you brew the tea: fairly weak, it tends to de-emphasize the whiskey’s alcohol; fairly strong, it contributes a sharpness of its own.

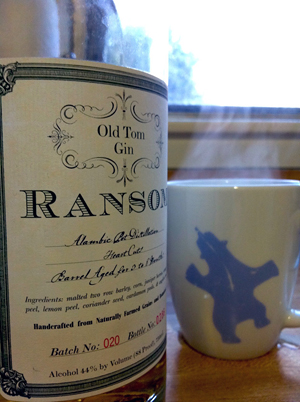

So that’s arrack, rum, and bourbon so far. You can make a hot toddy out of anything, though. Gin toddies were, to survey the literature, quite popular in the 19th century. You can really boost the time-travel factor by using some of the old tom gins that have come on the market as of late, riding the classic-cocktail revival. My favorite is Ransom, a conjectural recreation of the sort of gin that might have been floating around in Victorian times: a malted-barley base, barrel-aged, bright, forward botanicals.

Photo by Matthew Guerrieri

Old Tom Toddy

4 oz. water

2-4 tsp. sugar

Boil together. Pour over: 2 oz. old tom gin

The result: A toddy that obviates the need for added spices. The steam carries the botanicals straight into your head; the whiskey-like musty-caramel undertones finish off each sip in chewy style.

To drink an old tom gin toddy is to channel some essential part of the collective British palate. Mulled wine, brandy punches, hot beer (the list of traditional British hot beer drinks is long and fascinating)—I don’t think the people of the British Isles have ever met a type of alcohol they didn’t want to heat up and spice. Given the self-spicing nature of an old tom gin toddy, one gets a sense of why the British took so strongly to gin in the first place: it was pretty much a one-stop source for the flavors they had been cultivating for centuries.

All of these, however, are tangents to the classic hot toddy, the one Benjamin Silliman sampled (or merely observed), the simple triumvirate of whiskey, water, and sugar. Scotch has long been considered traditional for a hot toddy, so much so that it gave rise to an alternate origin of the name. From Charles Mackay’s A Dictionary of Lowland Scotch (1888):

In Allan Ramsay’s poem of “The Morning Interview,” published in 1721, occurs a description of a sumptuous entertainment or tea-party, in which it is said “that all the rich requisites are brought from far; the table from Japan, the tea from China, the sugar from Amazonia, or the West Indies; but that

Scotia does no such costly tribute bring,

Only some kettles full of Todian spring.”

To this passage Allan Ramsay himself appended the note—”The Todian spring, i.e. Tod’s well, which supplies Edinburgh with water.” Tod’s well and St. Anthony’s well, on the side of Arthur’s seat, were two of the wells which very scantily supplied the wants of Edinburgh; and when it is borne in mind that whiskey (see that word) derives its name from water, it is highly probable that Toddy in like manner was a facetious term for the pure element.

A stretch, certainly. But it does indicate the close relationship between Scotch whiskey and the hot toddy.

Still, I’m with Silliman’s hosts—single-malt scotch does seem a bit extravagant for the hot toddy, superb if you’re feeling flush, but otherwise somehow at odds with the drink’s talent for elevating humble ingredients. Straight rye is my hot toddy base of choice, the spirit’s natural spiciness and burn turned up by the heat and dressed up by the sugar.

But, to reiterate, that’s just me. And that’s the beauty of the hot toddy: it’s less of a cocktail than a template; at the same time, its resultant qualities—relaxation, stimulation, contemplation—are perfect for the pastime of trying to pin it down anyway. Argument and rumination are somehow made more civilized, more elegant, more satisfying. As Silliman observed, under the charm of the hot toddy, “it sometimes happens that a circle, before mute, becomes suddenly garrulous and brilliant.” Warm weather can wait.